Grief as Leverage: Using the Kübler-Ross Model as a Tool of Persuasion in Smoking Cessation

Thesis:

The Kübler-Ross model, originally conceived as a framework for understanding grief, can be recontextualized as a powerful tool for persuasion. When guiding individuals through transformational decisions—such as quitting smoking—the five stages of grief (Denial, Anger, Bargaining, Depression, Acceptance) can be intentionally leveraged to mirror the emotional journey of behavioral change. Recognizing, provoking, and guiding people through these stages allows for a structured, emotionally resonant strategy that moves them toward action.

Reframing the Stages

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross developed the five-stage model in 1969 to describe the emotional response to terminal illness and bereavement. Over time, it has been applied broadly to any significant loss or life transition. At its core, the model captures a non-linear, often recursive process of emotional reckoning.

In the domain of behavioral change—especially where addiction or deeply entrenched habits are concerned—this model has utility beyond empathy. It becomes strategic. People often experience the loss of a self-image, identity, or perceived control when confronting the need to change. The stages become not just reflections of internal experience, but predictable steps in a journey that can be guided.

Below, we explore how each stage can be used deliberately in a dialogue with a smoker, leading them toward the decision to quit.

1. Denial: Disarming the Illusion

Most smokers begin in a state of denial. This is not ignorance of smoking’s dangers; it’s selective disassociation. Common phrases include:

Most smokers begin in a state of denial. This is not ignorance of smoking’s dangers; it’s selective disassociation. Common phrases include:

-

“I can quit anytime.”

-

“I don’t smoke that much.”

-

“It’s my only vice.”

The purpose at this stage is not to counter facts with facts—those are already known. Instead, the goal is to pierce the narrative of invulnerability and provoke cognitive dissonance.

Example prompt:

“Something happens as you reach that realization about you and your habit of smoking. First, you don’t want to believe it’s true. You remember telling yourself, ‘I can quit anytime,’ and then when you try, you realize you’ve been trapped all along.”

Here, the persuasive move is to mirror the internal voice and then subvert it—highlighting the moment when personal belief fails under real-world testing.

2. Anger: Mobilizing Emotional Energy

Once denial is broken, anger surfaces. This is often directed inward (“How did I let it get this far?”), outward (“Why did they lie to me?”), or deflected (“My parents smoked; I never had a chance”).

Once denial is broken, anger surfaces. This is often directed inward (“How did I let it get this far?”), outward (“Why did they lie to me?”), or deflected (“My parents smoked; I never had a chance”).

Rather than defuse anger, this stage invites amplification—within ethical bounds. Anger has motivational potential; it energizes and disrupts homeostasis.

Example prompt:

“You’re right to feel angry. Angry at yourself for getting stuck in this deadly habit. Angry at the habit that’s turned you into its slave. Angry at the tobacco industry that promises freedom and sells you slavery.”

This rhetorical move legitimizes emotional upheaval and channels it toward an adversarial relationship with the habit itself. The goal is not to soothe but to ignite resolve.

3. Bargaining: Surfacing the Avoidance Patterns

This is the stage of rationalization. The smoker might say:

This is the stage of rationalization. The smoker might say:

-

“I’ll quit after this stressful project.”

-

“I’ll cut back first.”

-

“Vaping isn’t as bad—I’ll switch to that.”

Bargaining represents a pivot from raw emotion to mental negotiation. It’s a stall tactic masked as planning.

The persuader’s role here is to name the behavior—without shaming—and show its futility. The tone becomes diagnostic: you’ve seen this pattern before, and it doesn’t end where they think.

Example prompt:

“So you tell yourself you’ll quit tomorrow, or that it’s not that bad, or that you can still quit but you don’t want to right now. You’ll do it when you are in a better situation. And you are still stuck.”

By laying out the pattern and anticipating the excuses, you rob them of their power. The subject sees their own mind at work and begins to lose confidence in it as a reliable guide.

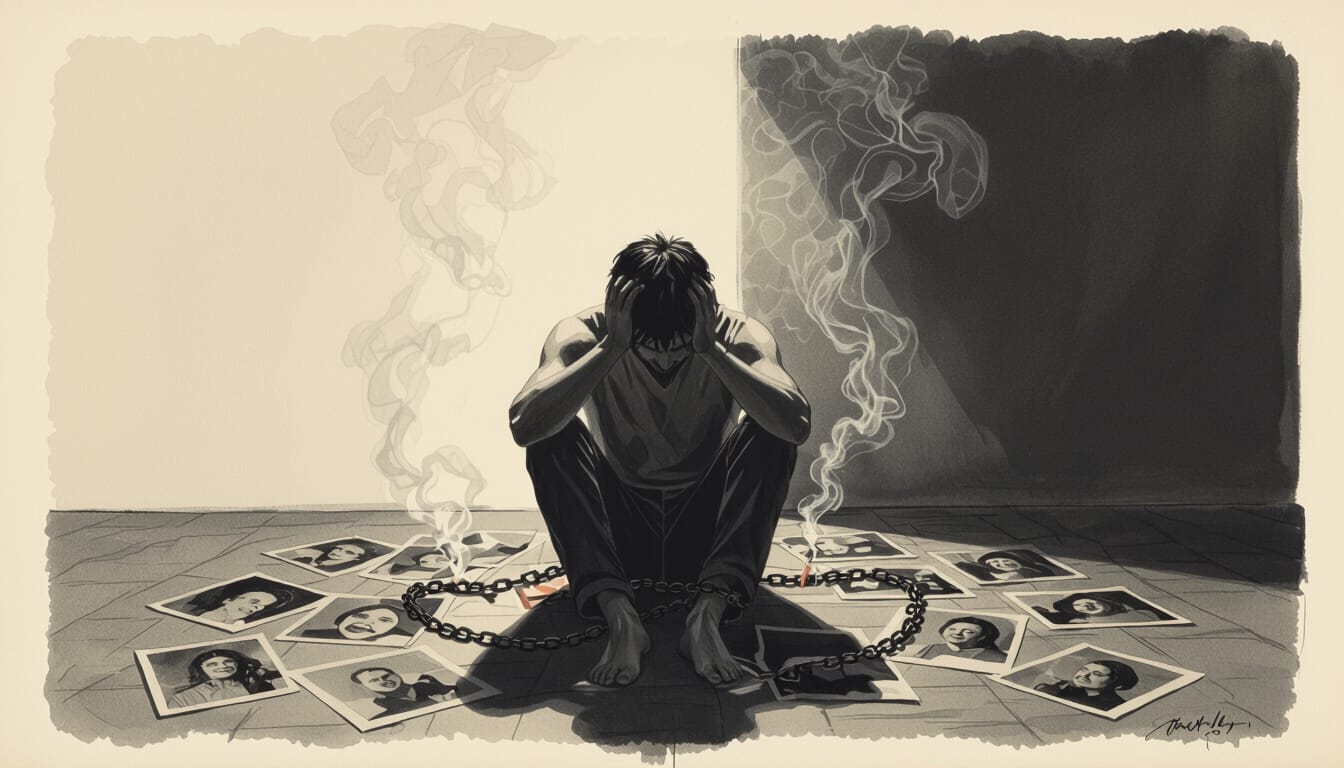

4. Depression: Holding the Mirror to the Cost

4. Depression: Holding the Mirror to the Cost

This is the moment of reckoning. No more bargaining, no more rage—just the weight of reality. The long-term cost becomes visible. Not just health, but time lost, identity confusion, and the sense of having surrendered agency.

The risk here is paralysis. Depression, left unchanneled, leads to resignation. The persuader’s job is not to fix the emotion but to validate it and frame it as a necessary passage.

Example framing:

“So, it’s hopeless. You’re stuck. You can’t do it.”

This deliberately bleak line functions like a low point in narrative structure. It creates a void—so that what comes next (Acceptance) feels earned. Importantly, this isn’t telling someone they’re hopeless—it’s voicing the thought they already have.

5. Acceptance: Empowering the Decision Point

5. Acceptance: Empowering the Decision Point

Acceptance is not surrender; it’s clarity. This is the stage where the internal chaos settles, and a person sees the situation as it is. Not ideal, not easy—but changeable.

Here, the message is simple, forward-facing, and declarative.

Example prompt:

“Your last and best decision is to just accept the fact you have to quit. You will quit. You are done with this roller coaster ride. The time is right NOW to stop this habit. Quit smoking and never go back.”

The persuasive strategy now is to anchor this moment of clarity as a decisive break. You’ve helped them grieve the loss of the fantasy that smoking wasn’t a problem. You now offer the promise of agency: not perfection, but movement.

Ethical Considerations

Using the Kübler-Ross model as a persuasion tool should be approached with caution. This framework manipulates emotional states—potentially powerful, but potentially coercive. It’s vital to ensure the person being persuaded retains autonomy and feels respected. The goal is not to exploit grief but to guide someone through an emotional arc they are already experiencing, often unconsciously.

This model also risks oversimplification. Not everyone follows the five stages linearly. Some skip stages. Some recycle through them multiple times. Rigid application can backfire. Flexibility and attunement to the individual are critical.

The Whole monologue of this process might sound like this:

“Something happens as you reach that realization about you and your habit of smoking. First you don’t want to believe it true. You remember telling yourself ‘I can quit at any time’ and then when you try, you realize you’ve been trapped all along.

You’re right to feel angry. Angry at yourself for getting stuck in this deadly habit. Angry at the habit that’s turned you into it’s slave. Angry at the tobacco industry that promises freedom and sells you slavery.

At that point it’s easy to try to negotiate your way out. So you tell yourself you’ll quit tomorrow, or that it’s not that bad, or that you can still quit but you don’t want to right now. You’ll do it when you are in a better situation. And you are still stuck.

So, it’s hopeless. You’re stuck. You can’t do it.

Your very last and very best decision is to just accept the fact you can JUST QUIT. You have to quit. You will quit. Accept it. You are done with the lies and excuses you tell yourself. You are done with this roller coaster ride. The time is right NOW to stop this habit. Quit Smoking and never go back.”

Conclusion

The five stages of grief offer more than a way to cope with loss—they offer a map of internal resistance. In the context of smoking cessation, they become a scaffold for persuasive dialogue. When used ethically and with skill, they allow the persuader to guide another person through denial, resistance, and avoidance—toward a self-chosen act of transformation.

Not by force. Not by manipulation. But by making the path visible, one emotional truth at a time.

4. Depression: Holding the Mirror to the Cost

4. Depression: Holding the Mirror to the Cost 5. Acceptance: Empowering the Decision Point

5. Acceptance: Empowering the Decision Point

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.